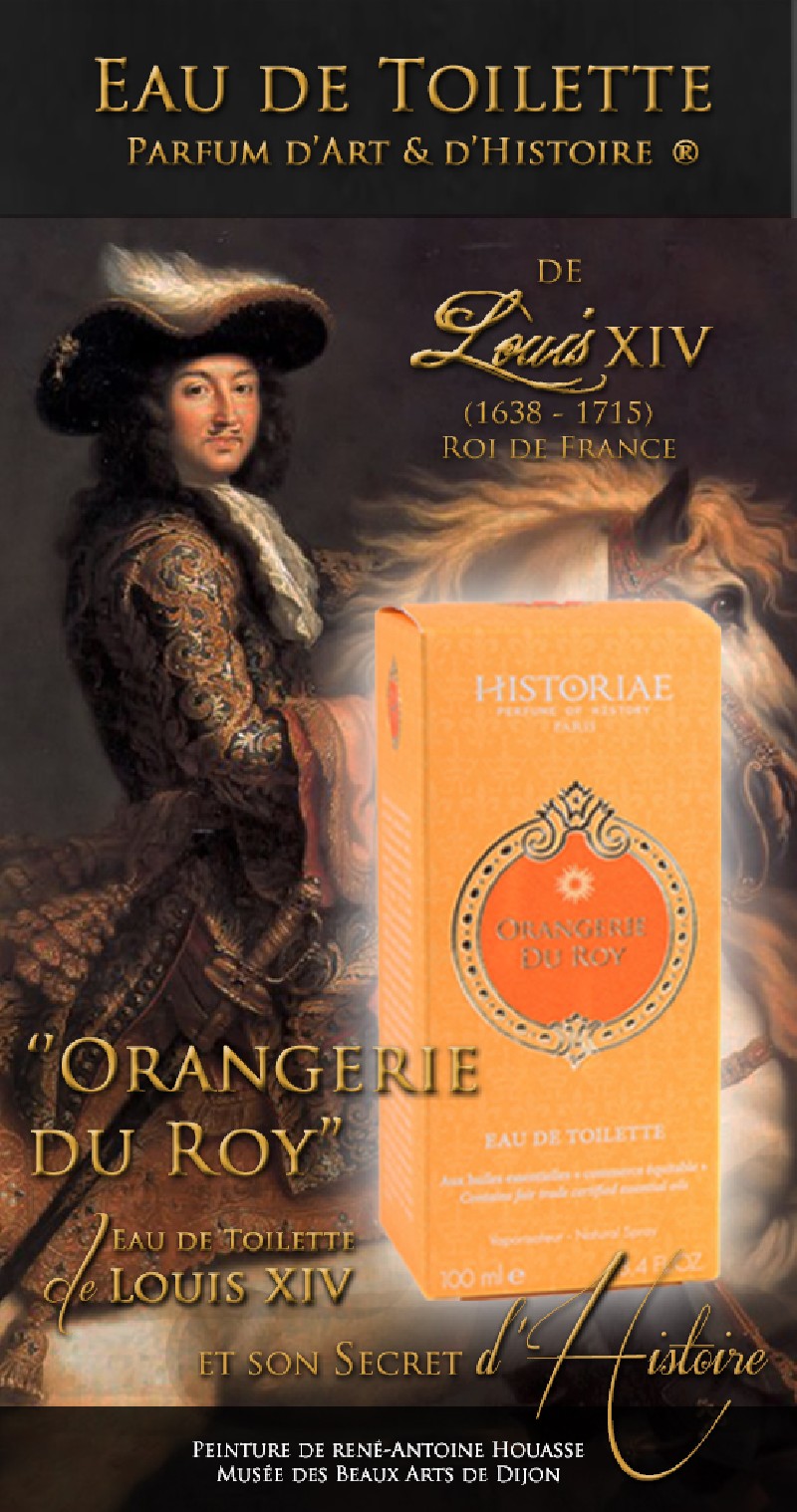

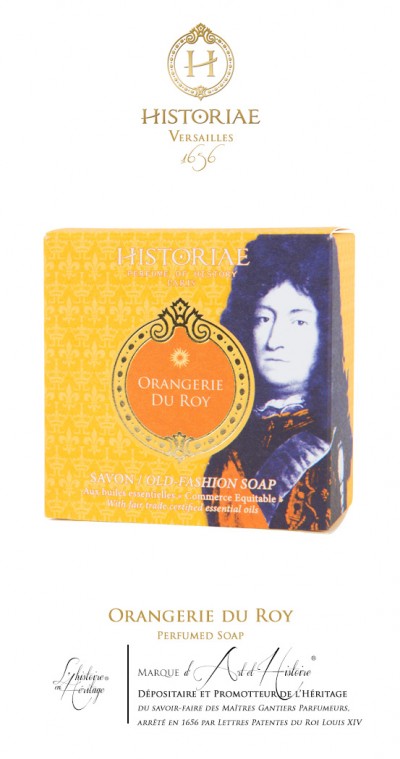

Orangerie du Roy - Eau de Toilette

reinterpreted Perfumes of History

Versailles, September 1rst 1689

"Orangerie du Roy" (The King's Orangery) is a perfume made from orange blossom and the favourite fragrance of King Louis XIV. The recipe is inspired by the mixing secrets of perfumer Simon Barbe - the perfumer of Dauphin and one of the most famous perfumers of the seventeenth century.

N° 741

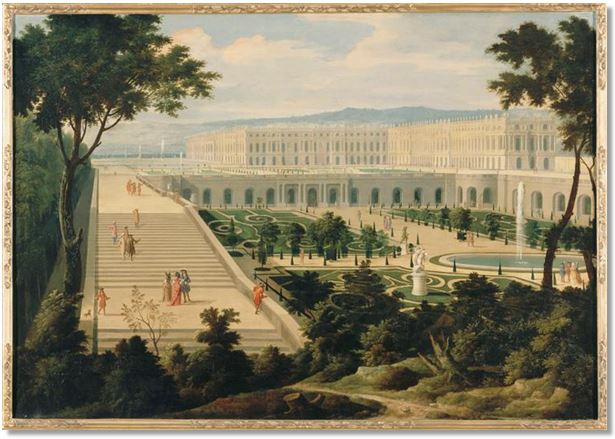

Versailles, The Castle of the Orange Trees

The 1st of September 1686 is an important day for French diplomacy: Louis XIV, hostile to Dutch commerce, ceremoniously received ambassadors to the King of Siam, Phra Narai, and intended to expand French influence all the way into the Far East, where Holland already had trading posts.

The exuberant feast laid out for the official reception of the Siamese diplomats was yet another sign of the Sun King’s glory, but also a sign of France’s recognition of Siam as a great Asian power: that kingdom situated between India and China, which fascinated the West with the refinement of its culture.

Although ill, Louis XIV received the ambassadors who had brought him a letter from the King Phra Narai. With unrestrained respect, they knelt before the King as before a living god, without daring to look at him. Louis XIV permitted them to look up, contrary to their custom. At the end of this audience, the Sun King was more than satisfied and as a sign of gratitude he gave them the honour of visiting his apartments and his gardens, in which the orangery had just been finished.

Fig.1.

The effect of this private visit was magisterial. One of the ambassadors exclaimed: ‘I knew before only three wonders - that of Man, God and Paradise. To this I now add a fourth - Versailles.’

Château de Versailles : A Backdrop of Orange Trees

Originally from Asia, the orange tree was introduced to Europe in the fifteenth century. Francois 1st had already built an orangery at Fontainebleau, but Louis XIV wanted to create an even more majestic backdrop for his orange trees, for which he had already reserved pride of place in the Chateau’s Hall of Mirrors: ‘Eight silver shafts from which chandeliers hang are placed between four silver pots in which orange trees stand, carried on bases of the same metal and ornamenting the spaces between the windows.’

They were to be shown off not only in this setting but also in the grounds of the chateau. Some little time after their installation at the Court of Versailles, Louis XIV asked Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the King’s primary architect, to build an Orangery, in the image of his glory and that of the Chateau of Versailles, in place of the small orangery built in 1663 by his predecessor, Louis Le Vau.

After two years of work, in 1686, the King’s Orangery saw the light of day. An architectural spectacle, the Orangery composed an outdoor garden and a building buried in the earth, structured around a central vaulted gallery 150m long and a towering 13m high, flanked by two wings, both 117m in size, which supported the two staircases, known as the ‘Hundred Steps’. The walls, which were 5m thick, protected the plants from draughts and maintained a constant temperature inside (which even in Winter was kept at 5 to 8 degrees Celsius.

The King’s Orangery was a place taken straight from a fairytale, the living theatre for a symphony of intoxicating scents from every country under the sun, without equal anywhere else in the world. At the heart of this orchestra reigned a luxuriant vegetation of almost tropical allure.

The place that the Great King had accorded to the orange trees had not escaped the notice of the Siamese ambassadors. ‘This is what made the first ambassador [from Siam] say that the magnificence of the King must be great to have such a superb building serve as the home for the orange trees. He added that there were many kings who could not match them in beauty.’

The Orange Tree : a refinement of France

To populate the Orangery, Louis XIV gathered all the orange trees from the royal houses and acquired new trees in Italy, Spain and Portugal. And he was soon able to pride himself in owning the largest collection in Europe.

Such was Louis XIV’s passion for the orange trees that he conferred nobility upon the Chinese shrub. Thus it was that from the seventeenth century onwards, in the wake of the sovereign, the orange tree became definitively associated with French refinement, as the 1685 work ‘The Delights of France’ relates: ‘One had to place the orange blossom around the beds, decorate the bedrooms with it, strew the alcoves with their flowers, crush them underfoot so as to release their scent; stuff the cushions with a thousand aromas, wash one’s hands and bathe in perfumed water, to put its flowers in the alcohol stills to extract its purest essence, and douse everything, including the serviettes, clothes, shrouds, shirts, tights, slippers and all the house furniture in its precious odours…

Where else would one find a more delightful country than France, where does not eat, sleep, wake or walk except on flowers, surrounded by fine scents? Am I not correct in saying that our incomparable State is a Paradise of delights for those who wish to satiate their senses and spend their lives enjoying its pleasures: for the Olfactory senses find such abundant material to satisfy them here.’

From this moment onwards, the essence distilled from orange blossom joined that of rose and jasmine, also sublimated by the King’s Orangery, in entering the History of the Court and into the composition of many perfumes and cosmetics.

Louis XIV : the secret perfumer

But there was more than the King’s passion for perfumes and odours behind his love for the orange tree and its flowers. After being initiated into the secrets of the Art of perfumery by his personal perfumer Martial, Louis XIV, just like an alchemist in search of the philosopher’s stone, locked himself away in his apothecary to prepare his aromatic concoctions in secret.

Unfortunately, he consumed so much perfume that he developed an allergy to it. The mere trace of a perfume was enough to trigger excruciating migraines. Only one scent remained an exception: orange blossom. The Duc de Saint Simon would repeat the tale in his memoirs: ‘Never has a man so loved odours only to fear them so profoundly after overindulging. With the exception of orange blossom, he could stand them no longer.’

Thus, orange blossom became the Louis XIV’s official perfume. After the pungent scents and heavy animal musks, ambers and civets that had dominated perfumes since the Renaissance and were used to mask bad odours and protect people from them, Louis XIV spearheaded a new olfactory fashion with orange blossom, one with elegant and fresh notes.

The Formula of the King's Orangery Eau

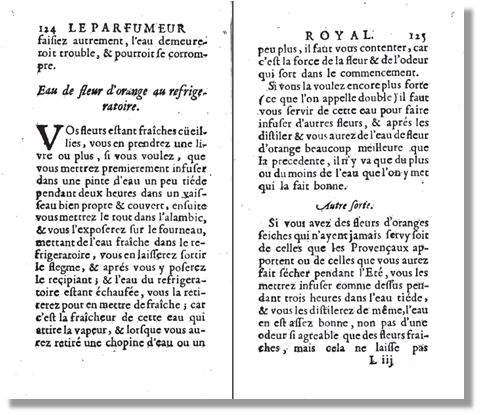

What was this distinctive odour that had so captivated the King that he added several drops to his drinks and sprayed his apartments with it using solid silver syringes? While several recipes have been exhumed from the buried secrets of History, there are uncertainties as to the exact formula used by Louis XIV. We can however reconstitute the logical sequences that permitted the orange blossom, whose flowers were used in the distillation of the eponymous perfume, to establish itself at court. This is thanks to several reference works, including ‘The Royal Perfumer’ by Simon Barbe, published in 1699:

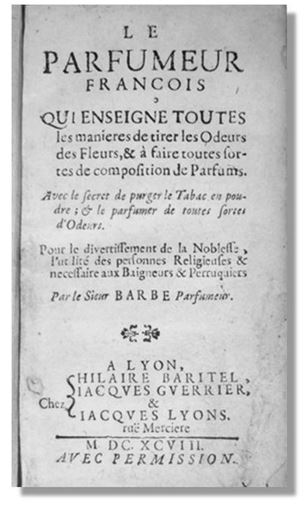

Simon Barbe, glove-maker and perfumer, conducted his commerce in Paris, rue des Gravilliers a la Toison d’Or, and was probably the most famous perfumer of his era. He wrote two perfumery manuals, in which he developed his knowledge and revealed his craft with great precision. The first of these, ‘The French Perfumer’, written for non-professionals with the intention of instructing all readers in the making of perfumes (particularly for the entertainment of nobles), was published in 1693.

His second work, ‘The Royal Perfumer’, was published in 1699, this time for professionals ‘who collect the flowers that are so necessary to glove-makers, wig-makers and liquor-merchants.’

Notes and references

[1] Mercure galant, décembre 1682, p. 6-13

[2] Mercure galant, novembre 1686

[3] François-Savinien d'ALQUIE, Les délices de la France, avec une description des provinces et des villes du royaume, Paris : G. de Luyne , 1685, p. 137.

[4] Stanis PEREZ, L’eau de fleur d’oranger à la cour de Louis XIV, Paris, Cour de France.fr, 2011. Article inédit publié en ligne le 1er août 2011 (http://cour-de-france.fr/article2031.html)

[5] Simon BARBE, Le Parfumeur royal, ou l’Art de parfumer avec les fleurs & composer toutes sortes de parfums, tant pour l’odeur que pour le goût, Paris ; Simon Augustin Brunet, 1699

Bibliograpy

Annick LE GUERER, Le Parfum, de origines à nos jours, Paris, 2005, Odile Jacob.Catherine DONZEL, le parfum, Paris, 2000, Chne.

André CHAUVIERE, Parfums et senteurs du Grand Siècle, Paris, 1999, Favre.

Iconography

Fig1. Jean-Baptiste Martin (1659–1735), L’orangerie du Château de Versailles, env 1695, Peinture sur huile, Château de Versailles

The perfume "Orangerie du Roy" draws inspiration for its composition from the work 'The Royal Perfumer', which was published in 1699 and contained an abundance of formulas and recipes for perfumes. The text is divided into nine treatises, of which the first is the 'Treatise for Perfumes and the most beautiful secrets involved in their composition'. The other treatises are dedicated, amongst other things, to soaps, hair powders, fragrances, pomades and scented liquors. There are also texts concerning gloves (approximately 40 different methods), fans, incense and beard wax.

The techniques of the seventeenth-century perfumery overlap with those used in the preparation of spirits (distillation and stills) and produced many different coloured compositions, using mineral, plant (flowers, spices, herbs, nuts, fruit peels) and animal elements.

With orange blossom, the "Orangerie du Roy" ushered in the fashion for the natural and the fresh, which was to become the trademark of perfumery in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Secret of Art : the extraction of orange blossom

Essence of orange blossom is an essential oil obtained by extraction via steam distillation of fresh flowers from the bitter orange blossom plant, Citrus bigaradia or the sweet orange blossom, Citrus aurantium.

The most popular is Néroli bigarade, which is taken from the flowers of the bigarade orange blossom. Most of the Néroli bigarade essential oil comes from Italy, Spain, Sicily, North Africa and the Grasse region in France.

The harvest and distillation of the flowers takes place from the end of April to the beginning of June in the Mediterranean region.

The yield varies according to weather conditions and extraction conditions. On average, one tonne of flowers gives one kilogram of essential oil, which explains the steep price for a small bottle of Néroli essential oil.

History of Perfumers, Secrets of Perfumers

" The soft caress of an orange blossom flower on the skin, cut when the sun is at its zenith and bathes the King's Orangery with light.

The first notes of Petitgrain suggest the willowy branches and green leaves of the King's orange blossom.

They are coloured by the acidulous touches of Orange, mixed with those of Lemon and of Bergamot, of Basil and Mint, added as an allusion to the aqua mirabilis of the era.

At its centre, the Orange blossom flower unfolds its silky petals. Their gilded shine, enriched by the honeyed aromas of Ylang-Ylang and Seringa, complement those of the Sun King. With but a murmur, it diffuses its precious perfume with honeysuckle echoes. Lavender and Thyme both punctuate all these white-petalled perfumes.

In the background, Patchouli, Vetiver and Oakmoss prolong this prior moment spent ambling between trees and their precious flowers. Their intoxicating scent cradles our every step. "

Bertrand Duchaufour

olfactory pyramid

Head notes : Lemon, sweet orange, petit grain, basil, Pearmint, bergamot

Heart notes: Orange blossom, ylang ylang, honeysuckle, lavender, thyme, mock orange

Base notes : Patchouli, vetiver, oak moss, musk

| Historicity : | reformulation et réinterprétation de compositions historiques à base de tubéreuse, inspirées par les carnets de composition et les recommandations des Grands Parfumeurs d’Art de l’époque de Marie-Antoinette, dont Jean-Louis Fargeon. |

| Concentration : | Eau de toilette |

| Capacity : | 15ml, 50 ml et 100 ml |

| Composition : | Essential Oils from Fair Trade |

| Fabrication : | French |

| Place of production : | France |

| Perfumer of Art : | Bertrand Duchaufour |

| Publisher of the Fragrance of Art : | HISTORIAE, Manufacture of Perfumes of Art and History |

Customers who bought this product also bought:

-

Orangerie du Roy - Home Fragrance

-

Rose de France - Eau de Toilette

-

Rose de France - Perfume Gift Box

-

Orangerie du Roy - Reed Diffuser (Sticks)

-

Violette Impériale - Reed Diffuser (Sticks)

-

Violette Impériale - Candle Gift Box

-

Rose de France - Reed Diffuser (sticks)

-

Marquise de Caumont - Pop Art Candle

-

Jardin le Nôtre - Eau de Parfum

Autres produits associés à "Objects of History of Louis XIV"

Wishlist

Top sellers

-

Jardin le Nôtre - Eau de Parfum

Reinterpreted Perfume Of History In order to celebrate the fourth...

10,00€ -

Bouquet du Trianon - Eau de Toilette

Reinterpreted Perfume Of History Versailles, 15th of August 1774 Art...

59,00€ -

Orangerie du Roy - Eau de Toilette

reinterpreted Perfumes of History Versailles, September 1rst 1689...

59,00€ -

Rose de France - Perfumed Soap

reinterpreted Scents of History Rose de France plunges us into the...

6,50€

Informations

Manufacturers

Suppliers

Viewed products

-

Orangerie du Roy - Eau de Toilette

reinterpreted Perfumes of History Versailles, September 1rst 1689...

No customer reviews for the moment.