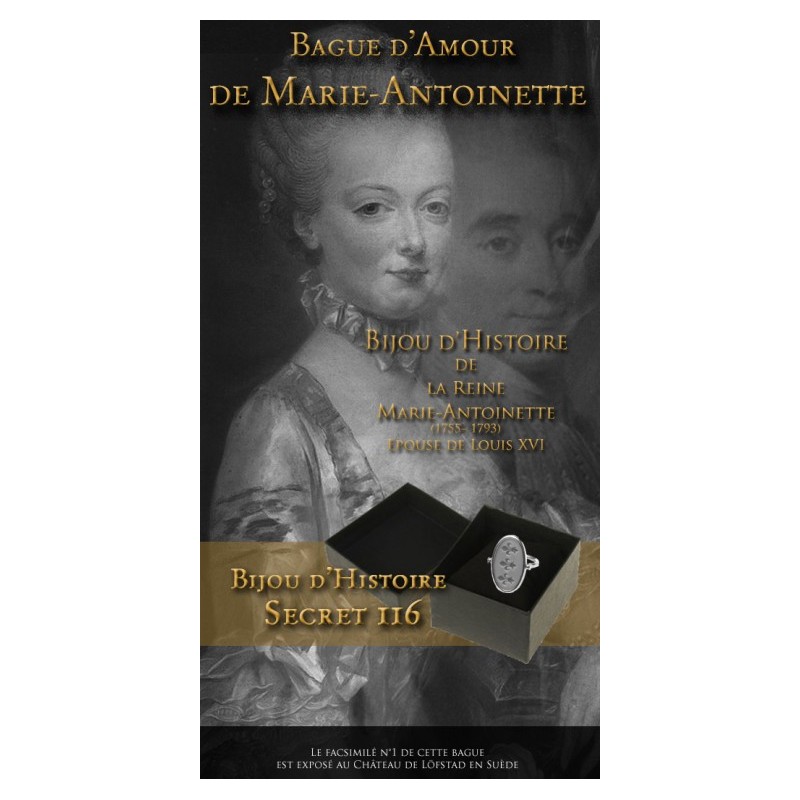

Marie-Antoinette's Love Ring to Axel de Fersen

This product is no longer in stock

Paris, Les Tuileries, 5 Septembre 1791

Reconstitution Historique

Marie-Antoinette et Axel de Fersen se rencontrent lors d'un bal masqué le 30 janvier 1774. Instant magique où, sous les déguisements, naît une histoire d’amour.

En 1791, emprisonnée, la reine envoie à son amant une bague d’amour...

N° 116

Marie-Antoinette's talisman ring

1791 marks the beginning of the tragic end of Marie-Antoinette and King Louis XVI.

After having attempted to escape East in secret to join Bouille’s royalist army at Metz, whose goal was to firmly restore them to the throne, the royal family - who had left the Tuileries palace on the night of 20th June 1791 - was arrested at Varennes on the 21st. Louis XVI was instantly stripped of his titles and the royal family, who were labelled traitors to the nation, were returned to Paris and placed under high surveillance at the Tuileries.

Confined to her residence and kept under strict surveillance, Queen Marie-Antoinette maintained a coded correspondence with several of her devotees. Indeed, while several aristocrats, such as the Comte d’Artois (brother of Louis XVI and the future Charles X), had opted for exile the day after 14th July 1789, some of them had remained loyal to their monarch and had risked their lives to do whatever necessary to save them.

Among these was the Hungarian Count Valentin Esterhazy, a particular favourite of the Queen. This ‘compatriot’, whom the Queen thus named because he was a subject of the Habsburg empire, served at once as an officer with foreign powers, but also (and most importantly) as an intermediary with the Swedish Count Axel de Fersen, organizer of the failed escape but also (as we now know for sure) the Queen’s lover.

On the 5th September 1791, Marie-Antoinette, trapped in the Tuileries, wrote an enigmatic letter to Esterhazy.

Marie-Antoinette's Love ring

This is what the letter says:

‘I am happy to have found an opportunity to send you a small ring which will surely be to your liking. It has been sold here prodigiously for the last three days, and the greatest pain has been had in procuring it. The ring wrapped in paper is for Him. Have Him wear it: it is exactly his size. I wore it for two days before wrapping it. Let Him know that it is from me. I do not know where he is. It is a terrible torment to be ignorant of the whereabouts of those we love.’

This letter followed a letter that had already been written to Esterhazy on the 11th August 1791: ‘If you write to Him, tell Him that neither land nor sea can separate two hearts: every day I become more certain of this fact.’

To whom does this mysterious ‘Him’, complete with capital H, refer? Evidently, Axel de Fersen, her lover. Long suspected but never formally established, this affair has recently been clearly proven thanks to the results of recent studies conducted on Marie-Antoinette’s coded letters. Letters which were not only coded, but also censored some time in the nineteenth century, probably by Fersen himself, his descendants or the custodians of his letters. A dip into Esterhazy’s correspondence gives significant insights into the meaning of this unique letter from 5 September 1791. Several weeks after the Queen wrote the letter, on the 21st October 1791, the Hungarian Count wrote to his wife from Saint-Petersburg, employing the same coded names as Marie-Antoinette to refer to the protagonists:

‘I received a letter from Avillart that Bercheny gave to Coblence, and which he gave to the emissary with a small gold ring that bore the engraving: Domine salvum fac regem et reginam; you might have seen it? He has written to me that it is in the letter which has been sent you, and has indicated to me the way to get my letters to him. [...] He has also sent me a ring for the darling. But I do not know where to get it. His letter is touching; it recommends that I do not believe in calumny and that I should never doubt the nobility of his way of thinking, nor his courage.’

“Avillart” referred to Marie-Antoinette and the ‘darling’ referred to Fersen. The fact has thus been established: Marie-Antoinette did indeed send two rings to Count Esterhazy, one of which was intended for the man whose absence caused her so much suffering. Contrary to appearances, there was nothing extraordinary about her sending a ring to one of her devotees. Indeed, many Royalists rushed to the Tuileries palace to obtain a keepsake from the Queen. As memoirs from that time testify, Marie-Antoinette thus gave rings with symbolic royalist inscriptions such as Domine salvum fac regem et reginam… (Lord, save the King and Queen), a verse from a Biblical psalm put into a motet to be sung during Mass in the Ancien Regime. This verse was sung since Louis XIII’s reign in the royal chapel and these words can still be seen in the inscription on the chapel ceiling, above the organ, in the Chateau of Versailles.

On the other hand, what most merits our attention in the hindsight afforded to us by History, is that in spite of the danger, and beyond all the precautions taken and the coding of the content, Marie-Antoinette revealed two secrets in her letter. First, the addressee was so dear to her heart that she wore the ring for two days before wrapping it. Second, she knew the precise size of his fingers. Consequently, the recipient of the ring, a man in this case (‘HIM’), had already been sufficiently intimate with the Queen, flouting all conventions and customs, to have most likely already made her wear one of his rings, or to have worn one of the rings belonging to the Queen.

What rings are these? In 1905, when Esterhazy’s Memoirs were published, the editor Ernest Daudet mentioned one ring which remained in the possession of Paul Bezeredj, great-grandson of Count Esterhazy. According to the annotator, it was ‘entirely in gold, dual-sided. On one side, three fleurs de lys are engraved; on the other, the inscription: ‘It is a coward who abandons them.’’

The slogan ‘It is a coward who abandons them’ was widespread in 1791 among the Royalists, who used it as a kind of rallying cry, in the form of a warning. According to his obituary in 1852, the Marquis de Villeneuve-Arifat mentioned in his recollections to his family that during their final meeting at the Tuileries, the Queen had offered him a ‘talismanic ring’ with this very inscription.

Lost in the labyrithns of History

It is impossible to know with the information at our disposal whether or not the ring intended for Axel de Fersen ever reached him, or if the ring offered to Esterhazy actually contains the two slogans together on one and the same ring: one (Domine salvum fac regem et reginam), mentioned in Esterhazy’s correspondence, which might have been engraved on the inside of the ring, and the other (as the ring passed down to Paul Bezeredj would seem to confirm), ‘It is a coward who abandons them’, engraved on the outside. That is the line we have taken, Count Esterhazy having possibly refused to mention the second slogan, judging it too royalist and compromising because it was well-known and suggestive. Verification, however, remains impossible; the ‘Esterhazy ring’ disappeared from circulation and only a photograph of it remains…

It little matters. With this ring, History has retained a magnificent talisman of love that a Queen on the edge of the abyss, aware of her tragic and inescapable destiny and tortured by the absence of the man she yearned for so secretly, had wanted to nourish with all her heart and soul for two days before releasing it, as one flings a bottle into the sea. An ‘I love you’ declared for eternity...

Jusqu'au bout, Fersen tentera de soustraire Marie-Antoinette à son sort funeste. C’est lui qui organisera et escortera "sa" reine lors de la fuite à Varennes, en 1791.

Après l’exécution de Marie-Antoinette le 16 octobre 1793, de retour dans son pays natal, Son amour pour Marie-Antoinette devint obsédant. Il ne se remettra jamais de sa mort.

Durant les 17 années qui suivirent la disparition de Marie-Antoinette, Fersen se plongera dans le monde des souvenirs. Retiré de la vie politique, comme en témoigne son journal, il s’isolera dans la maison familiale au centre de Stockholm et ne vivra plus qu’au rythme des commémorations et des anniversaires, tantôt celui de la mort du roi, tantôt celui de la fuite à Varennes, ou encore de l’anniversaire de la reine.

Il essayera par tous les moyens de récupérer des objets ayant appartenu à Marie-Antoinette. Sa tête ayant été mise à prix, il ne pourra malheureusement plus se rendre à Paris et il aura recours à des émissaires. Mais il ne récupérera que quelques objets, dont un couvre-lit que l’on peut voir au château de Löfstad.

La bague "à face cachée" de Marie-Antoinette

La bague de Marie-Antoinette à Fersen est une bague en or à chaton pivotant. La bague à chaton pivotant existait déjà dans l’Antiquité. Elle connut un regain de faveur au début de la période néoclassique.

L’Histoire a retenu que les bagues à chaton pivotant, permettant de cacher une inscription sentimentale, ont été mises à la mode par Marie-Antoinette après qu’elle les eut offert à Esterhazy et Fersen.

Il existe dans les collections des musées français plusieurs bagues utilisant la technique des chatons pivotant, notamment au musée des Arts décoratifs et au Château de Malmaison.

Les Propriétés "Magiques" de la Bague

Marie-Antoinette, qui était très superstitieuse, aura vraisemblablement trouvé dans cette pierre mille raisons de l’adresser à son amant.

La cornaline était utilisée en Egypte antique pour protéger le mort dans son passage dans l’au-delà. Depuis cette époque, on attache à la cornaline des propriétés particulières. Elle restaurerait la vitalité et la motivation, et éloignerait la peur de la mort. Elle calmerait aussi la colère, éloignerait les émotions négatives et redonnerait du courage.

De couleur rouge orangé à rouge sombre, la cornaline peut être facilement confondue avec de l’agate teintée. On fait cependant facilement la différence en regardant la couleur de la pierre. En effet, la cornaline est une pierre de couleur unie alors que l’agate teintée présente souvent des lignes multicolores.

Autres produits associés à "Objects of History of Marie-Antoinette"

Wishlist

Top sellers

-

Jardin le Nôtre - Eau de Parfum

Reinterpreted Perfume Of History In order to celebrate the fourth...

10,00€ -

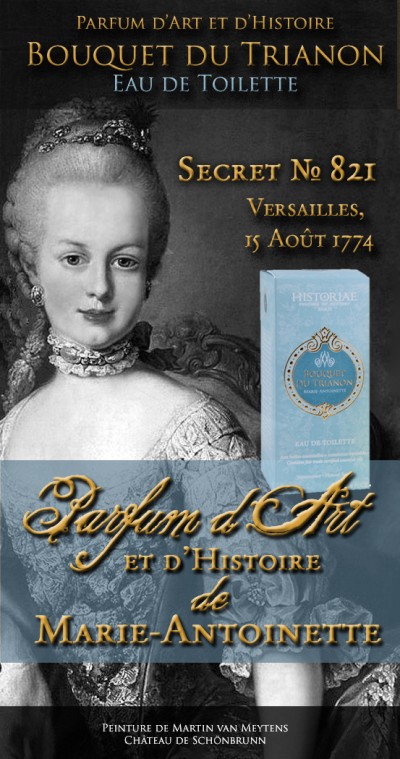

Bouquet du Trianon - Eau de Toilette

Reinterpreted Perfume Of History Versailles, 15th of August 1774 Art...

59,00€ -

Orangerie du Roy - Eau de Toilette

reinterpreted Perfumes of History Versailles, September 1rst 1689...

59,00€ -

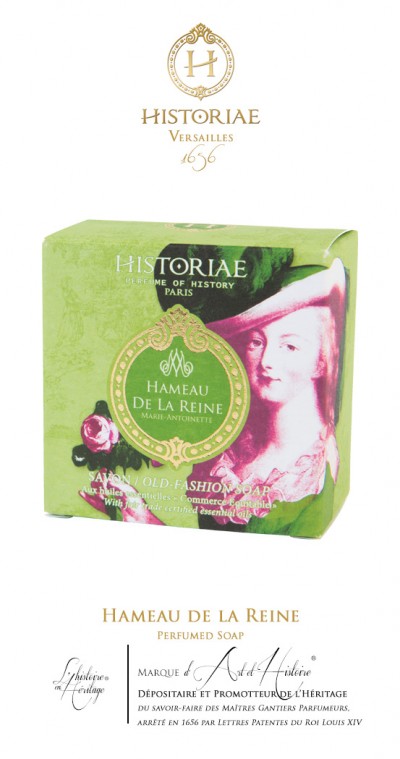

Rose de France - Perfumed Soap

reinterpreted Scents of History Rose de France plunges us into the...

6,50€

Informations

Manufacturers

Suppliers

Viewed products

-

Marie-Antoinette's Love Ring to Axel de Fersen

Paris, Les Tuileries, 5 Septembre 1791 Reconstitution Historique...

No customer reviews for the moment.